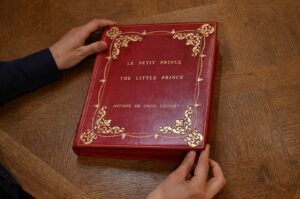

History, they say, never travels in a straight line. It curls back upon itself, zigzags and loops, stubbornly refusing the linear clarity we so desperately seek. Veteran Turkish journalist Sadık Albayrak’s “Meşrutiyet’ten Cumhuriyet’e Meşihat-Şeriat-Tarikat Kavgası” (“From the Constitutional Monarchy to the Republic: The Struggle of the Religious Authority, Sharia and Tariqa”) plunges us headfirst into one of these serpentine turns in Turkish history, where politics, religion and modernity clashed not only on paper but in the streets, the courts and – perhaps most tragically – on the gallows. To read this book is to watch a nation struggle with the weight of its past while straining toward the future. It is both an autopsy and a prayer.

From the first page, the book, now republished as a single volume after an earlier three-part series, confronts readers with an image so arresting that it could serve as a metaphor for the entire narrative: 98-year-old Erbilli Esad Efendi, accused of involvement in the tragic Menemen incident in recent Turkish history, dragged from his home by gendarmerie officers and executed alongside his son. This photograph, Albayrak writes, is a visual thesis. It encapsulates the cruel intersection of politics and faith during Türkiye’s transitional years. A single image, yet it speaks volumes about a nation’s collective trauma.

Albayrak’s prose is steeped in both melancholy and defiance. He writes with the fervor of a man who has spent decades battling the tides of intellectual resistance. His own life mirrors the turmoil of the period he chronicles. The “kavga” (“struggle”) in the book’s title seems to refer as much to his personal battles – facing lawsuits, censorship and societal backlash – as it does to the broader ideological conflicts of the late Ottoman and early Republican eras. Albayrak is no mere intellectual; he is a participant.

The book’s structure is ambitious, weaving together historical analysis, political critique and cultural commentary. The 83-year-old Turkish writer revisits themes explored in his earlier works, such as “Sömürüye Karşı İslâm” (“Islam against Exploitation”), but with a more expansive lens. He draws heavily on newspapers, journals and first-hand accounts from the period, painting a realistic picture of a society in flux. The tension between tradition and reform is omnipresent. Religious institutions, once unshakable pillars of Ottoman life, were subjected to intense scrutiny and, often, outright dismantling. The Second Constitutional Era, with its promises of parliamentary governance, unleashed a cacophony of voices – conservatives, secularists, modernists – all vying to shape the nation’s soul.

What distinguishes this book from conventional historical narratives is its refusal to sanitize the past. Albayrak is unflinching in his portrayal of the Tanzimat and Meşrutiyet periods. He describes, with near-cinematic detail, the trials of “ulema” (“Islamic scholars”) and the forced exile of religious leaders. The book is not presented as an abstract ideological debate but as a visceral, often brutal reality. The reader feels the weight of the stakes: This was a battle for the heart of a nation, with profound implications for its identity and future.

One of the book’s most striking sections explores the role of the press during this turbulent era. Albayrak laments the dominance of Westernized, secular voices in newspapers and magazines, noting that Islamic perspectives were relegated to the margins. Weekly and monthly journals such as “Sebilürreşad” and “Beyanü’l-Hak” emerge as heroic outliers, grappling with monumental questions of governance, ethics and faith. Albayrak’s critique is sharp but fair; he acknowledges the shortcomings within the Islamic intellectual community while railing against the systemic suppression they faced.

Yet, for all its historical depth, the book is not without its challenges. Albayrak’s writing can be dense, and his passion occasionally veers into polemic. Readers unfamiliar with the complicated web of Ottoman and Turkish political history may find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer volume of references and allusions. This is not a book for the casual reader; it demands patience and engagement. But those who persevere will be rewarded with insights that transcend the specificities of time and place.

In the book’s foreword, Albayrak reflects on his career, noting the persistent “prangalar” (“shackles”) imposed on thought and expression in Türkiye. This sentiment is felt throughout the text. The struggles of the late Ottoman and early Republican periods are not relics of the past; they echo in contemporary debates about religion, governance and identity. Albayrak’s work serves as both a historical document and a cautionary tale, reminding us that the “kavga” is never truly over.

By the book’s conclusion, Albayrak leaves us with a sobering but hopeful message. He writes that the true strength of a nation lies not in its ability to suppress dissent but in its capacity to engage with it. The rediscovery and reinterpretation of Islamic institutions, he argues, are not acts of regression but of renewal, offering a path toward a more inclusive and authentic understanding of Turkish identity.

Ultimately, “Meşrutiyet’ten Cumhuriyet’e Meşihat-Şeriat-Tarikat Kavgası” is a great work – part history, part manifesto and part lament. It is a book that demands to be read slowly, savored and debated. Albayrak has given us more than a chronicle of a nation’s past; he has given us a mirror in which to see our present and perhaps, if we dare, our future.

Be First to Comment