Countries make significant investments to enhance their citizens’ access to education. Following the massification of education, discussions on education quality, equitable access to quality education for all segments of society and equal opportunities in education have become central to educational debates. In particular, the past decades have increasingly highlighted the relationship between education and the economy through human capital, pushing countries into a competitive race in education as a proxy for economic competition.

Each education system exists within a broader ecosystem and climate as a whole. Thus, there is a sociocultural context in which the system operates and its components function. When this context is overlooked, policy changes based on the direct transfer of best practices from other countries often fail to produce the expected outcomes or result in outright failure. This is precisely what happens in many countries. In particular, low-performing countries attempt to borrow and integrate certain components of high-performing education systems into their own, expecting improvements. However, the desired results remain elusive.

Each component of a system functions efficiently within its own contextual framework. Ignoring this context and transplanting only a part of one system into another will not achieve the intended goals. Therefore, education policies that draw on international experiences while fairly evaluating the existing education system within its own context are more likely to yield successful outcomes.

A whole system

From early childhood education to higher education, all levels of education form an interconnected and dynamic system. Issues at any level not only affect that specific stage but have implications for the entire system. Therefore, the most critical aspect of developing education policies is to focus on maintaining the integrity of the education system as a whole. Improvements made with this perspective will contribute to the overall enhancement of the system. For example, reforms in the transition to higher education that take the entire system into account will not only facilitate access to higher education but also lead to improvements in the secondary education system.

In an alternative approach, despite being a single entity, the system would be fragmented, leading to a lack of coherence and misalignment, where different parts speak different “languages.” In such cases, the cost of changes made in one component would be borne by other parts of the system. Therefore, when education policies consider systemic alignment, they not only improve the targeted area but also help resolve many issues across the broader system. Conversely, when systemic alignment is ignored, the policies implemented may create new problems in different areas of the education system.

Our country, Türkiye, has suffered greatly from this fragmented structure and systemic misalignment. For example, the coefficient system, which was introduced in 1999 and abolished in 2012, was far more than a mere technical change in the transition to higher education – it generated massive costs at both primary and secondary education levels. Clustering academically successful students into specific types of high schools deepened disparities in school performance and exacerbated educational inequality. It also led to a decline in the quality of vocational education, making it difficult for the labor market to find the skilled workforce it needed, resulting in significant economic costs. Similarly, policies aimed at restricting access to higher education intensified competition at the secondary level, diverting the focus of education from its broader context.

Although different institutions are formally responsible for various aspects of the education system, all processes naturally affect the entire system and its overall quality. While institutions and organizations within the education system may have responsibilities tied to specific educational levels, it is essential to recognize that their ultimate responsibility extends to the system as a whole. When these institutions support one another and prioritize systemic alignment, the overall quality of education can improve holistically. Therefore, ensuring systemic coherence in education policies is of utmost importance.

Out-of-school factors

Educational equity is not only about access to education but also about the quality of what is accessed. The responsibility of education systems does not end with providing access to education; it also includes ensuring that the quality gap between available educational services is minimized as much as possible. Therefore, education policies should aim both to improve the quality of education and to reduce inequalities. When discussing the causes of educational inequalities and disparities in school performance, both in-school and out-of-school factors must be considered together, as they jointly shape educational outcomes. A significant portion of out-of-school factors is linked to families’ socioeconomic status and socio-cultural capital. In this context, various parameters – such as family income level, parental education, time devoted to children and the availability of books and resources at home – collectively determine the family’s socioeconomic status.

Numerous studies highlight the strong correlation between socioeconomic status and student achievement. Students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds tend to perform better. Consequently, in many education systems, socioeconomic status is the primary driver of disparities in student performance. If, at any stage of education, some students gain an additional advantage due to out-of-school factors – meaning that inequalities stemming from external conditions further amplify existing advantages – the Matthew Effect comes into play.

First introduced by sociologist Robert K. Merton (1968), the Matthew Effect derives its name from a verse in the Gospel of Matthew: “For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance.” Initially used to describe the accumulation of advantages in academia, the term has since been applied across various fields to explain how advantages reinforce themselves, leading to further advantages. According to the Matthew Effect, previous successes shape future successes, just as past disadvantages, if left unaddressed, can lead to further failures. In education, this concept has been widely used since the 1960s, starting with the work of James S. Coleman in the United States and later developed by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu to explain the latent dynamics of academic achievement. Beyond education, the Matthew Effect manifests in all areas where inequalities are reproduced. In contexts where this effect is at play, the distribution of resources, achievements and rewards becomes highly skewed, and these disparities can persist throughout a person’s lifetime.

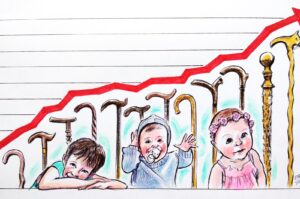

In this context, the most effective education policy for reducing inequalities caused by out-of-school factors is the expansion of early childhood education. Research has consistently shown that early childhood education plays a crucial role in shaping students’ future academic success. By fostering cognitive, social and emotional skills, early childhood education enhances learning efficiency in the long run. Moreover, a significant portion of academic achievement gaps linked to socioeconomic status emerge during early childhood. As a result, disparities in school readiness at the start of primary education arise based on access to early childhood education. These initial differences in preparedness exacerbate academic achievement gaps over time, widening as students progress through the education system.

Investments aimed at increasing access to early childhood education yield significantly higher social returns compared to interventions made at later stages of education while also requiring much lower investment costs. The challenges arising from insufficient access to early childhood education not only become more difficult to resolve in the later stages of education but also become increasingly costly to address. Considering that access to early childhood education decreases as socioeconomic status declines, targeted policies to enhance access for disadvantaged groups can reduce educational inequalities at a lower cost and before they become entrenched.

In this regard, effective education reforms should focus on minimizing the impact of out-of-school factors on academic achievement, even if they cannot eliminate these effects entirely. Otherwise, without addressing these structural issues and implementing the necessary improvements, reforms or policy measures that reduce the problem to an individual level and focus solely on the school environment are unlikely to succeed.

In sum, the education system must be viewed holistically in developing education policies, from early childhood education to higher education, with systemic alignment at the core of every policy. Any intervention at one level must be evaluated in terms of the potential costs and impacts it may generate at preceding and subsequent levels. At the same time, it is essential to recognize that in-school and out-of-school environments form an integrated whole and that out-of-school factors are just as critical as the school itself. By considering these two dimensions, it becomes possible to develop more effective, impactful and efficient education policies that yield sustainable results.

Be First to Comment