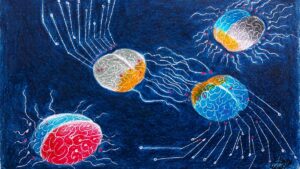

The global socio-economic landscape is undergoing a profound transformation. With the decline of traditional power structures and the emergence of new global players, the world has entered an era of multipolarity. This shift is not only political but also economic, with new dominant forces reshaping global markets and the flow of information. Among these forces, the rise of techno-oligarchies – concentrated networks of technological elites – has become a defining characteristic of the contemporary world order. These techno-oligarchs, wielding immense power through the control of digital infrastructure, data and technological innovation, are challenging the conventional boundaries of governance, power and societal organization.

At this very point, it should be understood that it was a necessity of the zeitgeist that U.S. President Donald Trump chose Elon Musk, one of the most well-known techno-oligarchs in the world, who is among the founders of companies such as Open AI and Paypal, and who currently controls giant technology investments such as X (formerly Twitter), Optimus Robots and Tesla, as his adviser. However, it should not be forgotten that Elon Musk’s ability to show off by coming to the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) with a chainsaw in his hand is not because of Trump’s but because of his own power as a techno-oligarch.

Defining new elite

Historically, the global order has been shaped by dominant powers – imperial powers in the past and superpowers during the Cold War. The 21st century, however, has ushered in a new era where power is distributed among multiple centers of influence. This multipolar world is marked by the rise of emerging economies, the reassertion of regional powers, and the increasingly important role of non-state actors, especially multinational corporations and tech giants. While traditional geopolitical alignments like EU, BRICS and NATO remain significant, the economy and global influence are no longer dominated by a handful of powerful nations. Instead, influence is increasingly diffused across countries, regions and powerful corporations, especially those in the technology sector.

The term “techno-oligarchy” refers to a socio-economic class of wealthy and influential individuals or entities that control key aspects of technological development and its applications. These elites are typically at the helm of major tech companies, digital platforms and innovation hubs. They not only possess substantial economic power but also influence political systems, culture and social dynamics through their control of data, communication and technological infrastructure.

The most prominent examples of this techno-oligarchy are the leaders of major tech corporations – such as Amazon, Google, Apple, Facebook (Meta) and Microsoft – as well as emerging Chinese tech giants like Alibaba and Tencent. These companies have become powerful enough to shape global markets, influence consumer behavior and even sway political decisions. Unlike traditional oligarchies, which rely on the control of natural resources or capital, techno-oligarchies derive their power from the ownership and manipulation of information, algorithms and digital ecosystems. Alibaba’s shares rose 14.56% when the company pledged to make “aggressive” investments in artificial intelligence and cloud computing over the next three years. This should be seen as a concrete indicator of all these developments. It should not be forgotten that the money markets are the first to buy or turn away from all social, economic and political developments in the world.

Concept of techno-oligarchy

In a multipolar world, techno-oligarchies transcend national borders, operating in a global space where they influence various countries and regions differently. The interdependence of economies, the cross-border flow of data, and the global reach of digital platforms have made the traditional nation-state less effective in controlling the forces that shape its own future. This has opened up space for techno-oligarchies to operate as quasi-sovereign entities, able to influence the direction of nations and their economies, sociologies even wars in ways that were unimaginable just a few decades ago.

For instance, major technology companies are increasingly involved in shaping policies related to privacy, cybersecurity and even international trade. The data-driven business models of companies like Facebook and Google allow them to manipulate public opinion and consumer behavior on a scale that rivals traditional media empires. Additionally, their influence extends to legislative matters, with lobbying efforts influencing laws related to digital monopolies, intellectual property rights and global data governance.

In countries like China, the government has developed a closer relationship with tech firms, giving rise to what could be termed a “state-driven techno-oligarchy.” Here, the state collaborates with technological elites to advance national interests, leading to the creation of powerful state-backed enterprises like Huawei and Tencent that not only dominate China’s tech industry but are also expanding globally. In the U.S. and Europe, meanwhile, tech giants are exerting soft power by promoting democratic ideals and free-market principles – sometimes at the cost of regulation and transparency.

With the Russia-Ukraine war still ongoing, Elon Musk could reportedly cut off access to Starlink satellites from Ukraine after President Donald Trump’s less-than-enthusiastic response to Ukraine’s request for rare earths. This exclusive news was reported in Reuters as “Exclusive: US could cut Ukraine’s access to SpaceX owned Starlink internet services over minerals, say sources By Andrea Shalal and Joey Roulette.”

Democracy, equity challenged

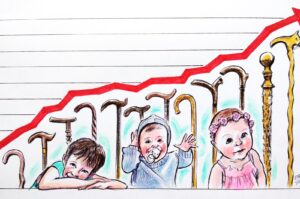

While techno-oligarchies drive innovation and economic growth, they also pose significant challenges to democracy and social equity. The concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few digital elites undermines social mobility and exacerbates income inequality. In a world where data is the new oil, the monopoly over data collection and analysis gives these entities not just wealth, but the ability to shape the very nature of human interaction, thought and behavior.

Moreover, these oligarchies often operate beyond the reach of national governments, escaping regulation and accountability. The role of large tech companies in elections, the dissemination of disinformation, and the surveillance of private citizens have raised serious concerns about privacy, human rights, and the integrity of democratic processes. The result is an emerging crisis of governance, where traditional forms of state authority struggle to keep up with the pace and reach of technological development. The recent Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal has brought into question a major question about how a technology company can influence people’s perceptions of candidates in elections.

As the techno-oligarchy continues to consolidate power, two potential futures emerge. On the one hand, there is the possibility of technological governance – a future where global technology companies partner with states and international bodies to create a fairer, more equitable global society. In this scenario, tech companies could play a leading role in solving global issues such as climate change, inequality and access to health care, leveraging their resources and expertise for the collective good.

On the other hand, we might face a future of technological totalitarianism. In this dystopian vision, the power of the techno-oligarchy goes unchecked, leading to a world where “corporations,” not states, dictate the rules of the game. In this scenario, surveillance capitalism, the erosion of personal freedoms, and the monopolization of knowledge and power could lead to an uneven, stratified global society where the few control the future of the many.

It will be observed that the world’s largest asset managers such as BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street Global Advisors, Fidelity Investments, Capital Group, Amundi, PIMCO, Franklin Templeton, Invesco and T. Rowe Price will increase their investments in AI and robotics much more than expected or at least they should do so. Because the point to keep in mind is that AI is not “part of the future,” but the future itself.

In a multipolar world where power is distributed across a network of diverse actors, these elites wield unprecedented control over information, technology and the very fabric of modern life. Whether this influence will lead to greater equity or exacerbate the divides in society remains uncertain. What is clear, however, is that the role of technology in shaping the future is no longer just about innovation; it is about power – how it is created, controlled and used in an ever-evolving global landscape.

Be First to Comment