When Kyrgyz President Sadyr Zhaparov and Tajik President Emomali Rahmon exchanged firm hugs after signing a historic border treaty last week, they signaled relief over resolving one of post-Soviet Eurasia’s most intractable disputes – a 33-year conflict that turned their shared frontier into a violent flashpoint. The March 13 agreement demarcates the entire Kyrgyz-Tajik border, ending a crisis that killed hundreds, displaced tens of thousands and risked destabilizing a region critical to global energy transitions.

The treaty’s significance lies in the political courage required to achieve it. Zhaparov and Rahmon prioritized stability over territorial claims. Askat Alagozov, spokesperson for Kyrgyzstan’s presidency, remarked: “This agreement is the fruit of political will. The issue festered for over a century. Its resolution opens a path to friendship, cooperation and economic development.”

Cartographic quagmire

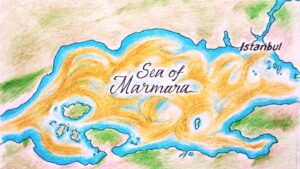

The Kyrgyz-Tajik border is a relic of Soviet mapmaking since Moscow’s bureaucrats hastily divided the region into republics with little regard for ethnic and ancestral communities or common water sources. Villages were split, water sources straddled jurisdictions and nomadic traditions collided with arbitrary lines.

When the USSR dissolved in 1991, the two countries inherited these flawed boundaries. They were never meant to be international and relied on different Soviet administrative maps – leading to conflicting territorial claims. Rival claims intensified, occasionally erupting into violence, with the most alarming incident being the short but deadly conflict in September 2022 – an escalation that convinced both governments that delay was no longer an option.

Ferghana Valley, a densely populated basin shared by both nations, bore the brunt. Over 150 clashes have erupted in the last 10 years, often sparked by farmers disputing water access or shepherds grazing livestock on contested land. The deadliest violence occurred in September 2022, when Tajik forces installed surveillance cameras near a water facility in the Vorukh exclave, igniting artillery battles that killed at least 100 people and displaced 100,000.

Mechanics of compromise

In this context, for Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – among Eurasia’s poorest states – reopening the border was an urgent necessity.

The historic border treaty finalizes the demarcation of the entire border, ending reliance on disputed Soviet records. Key provisions include a few aspects. The first among these is full border recognition with the 1,006-kilometer (625-mile) frontier, with 520 kilometers settled by 2011 and the remaining 486 finalized over the past three years. The second is reopening the trade routes with an immediate resumption of operations at the Kyzyl-Bel and Kairaghach checkpoints, which have been closed since 2021. The last is the shared water management with a bilateral commission to oversee the Isfara River Basin, a recurring flashpoint.

Millions were lost when crossing points closed in 2021, and bilateral trade all but collapsed. Officials now hope to see trade soar to $500 million by 2030, up from a meager $12 million in 2023 and $1.7 million in 2024. Hours after the treaty was signed, crowds surged through the reopened Kairagach crossing. Additionally, newly resumed flights between the capitals and proposed routes, such as Dushanbe-Tamchi in summer, promise to boost cultural and commercial ties.

“This step will significantly contribute to strengthening security, stability and sustainable development not only for our states but for the entire Central Asian region,” said Zhaparov at the signing ceremony.

Rahmon, who has ruled Tajikistan since 1994, struck a conciliatory tone. “The border treaty will create a solid foundation for further strengthening interstate relations,” he said. “Today, we open a new page.”

But economics alone did not drive this accord. Climate change exacerbates the stakes. The Ak Suu/Isfara River, vital to both nations, has seen its glaciers shrink by 17% since the 1950s, according to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reports. Water allocations from the Golovnoy intake – a contested site during clashes in 2021 – have become a matter of survival for downstream communities. By creating a framework for equitable water sharing, the treaty underscores how resource cooperation can avert future conflict in a rapidly warming world.

The turning point

According to Bishkek-based analyst Emil Juraev, the brutality of last year’s four-day war was a wake-up call. “Leaders realized a quick resolution was necessary after the clashes in 2022,” he said. Swift negotiations followed, but the road to this agreement was marked by painful compromises. The agreement included land swaps, notably around the Tajik enclave of Vorukh, and the relocation of villagers to address the complexities of ethnic enclaves. Acknowledging these sacrifices, Alagozov stressed the state’s responsibility to support those “who showed true patriotism.”

Far from an isolated success, the accord builds on a 2021 breakthrough between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan that similarly resolved a Soviet-era border impasse through dialogue. Together, these achievements suggest that Central Asian nations are now tackling their own disputes rather than relying on outside mediation.

Yet it’s crucial to see beyond this single treaty. For one, the risk of future conflicts in Central Asia has dropped significantly; second, newly forged economic and neighborly ties stand to reshape trade and cooperation; and third, the region’s last ambiguous border has finally been laid to rest.

Meanwhile, consolidation among Turkic states is gaining momentum – a shift set to go throughout Central Asia, the South Caucasus and even Türkiye. Still, local ownership has remained the driving force behind this settlement. International partners praised the agreement, as Alagozov cited congratulatory messages from Russia, the U.S., Türkiye and multilateral organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). Their endorsements frame the deal as a diplomatic triumph – but its real power may lie in how decisively it affirms that the region can solve its own problems.

Be First to Comment